Diagnosing Cushing's

Cushing’s can seem challenging to diagnose, with vague clinical signs. It can leave us feeling uncertain, despite sometimes multiple rounds of diagnostic tests.

This section will help you to be confident when you have a Cushing’s case in front of you, from the signalment, clinical signs and initial work up even before endocrine testing, minimising confusion and frustration.

There are still significant numbers of suspected - but not confirmed cases of Cushing's.

For every

100

that are treated...

There are another

57

where Cushing's is suspected but not confirmed

How are cases missed?

Clinical signs attributed to "just getting old"

Patients present at different stages so early signs might be less pronounced

Lack of confidence in diagnostic testing

Cost increases if multiple diagnostic tests are needed

Build the case

Consider the patient’s signalment and clinical signs, do they increase your suspicion of Cushing’s?

Your patient may present with one or many of the clinical signs, any combination could indicate Cushing’s.

How to recognise Cushing's?

Diagnosis for Cushing's doesn't need to be complicated, diagnosis can be simple. Dogs are being diagnosed increasingly earlier in the disease process and often do not display all the 'P' signs at initial presentation. Any combination of symptoms could indicate Cushing's.

addIncreasing suspicion: common findings

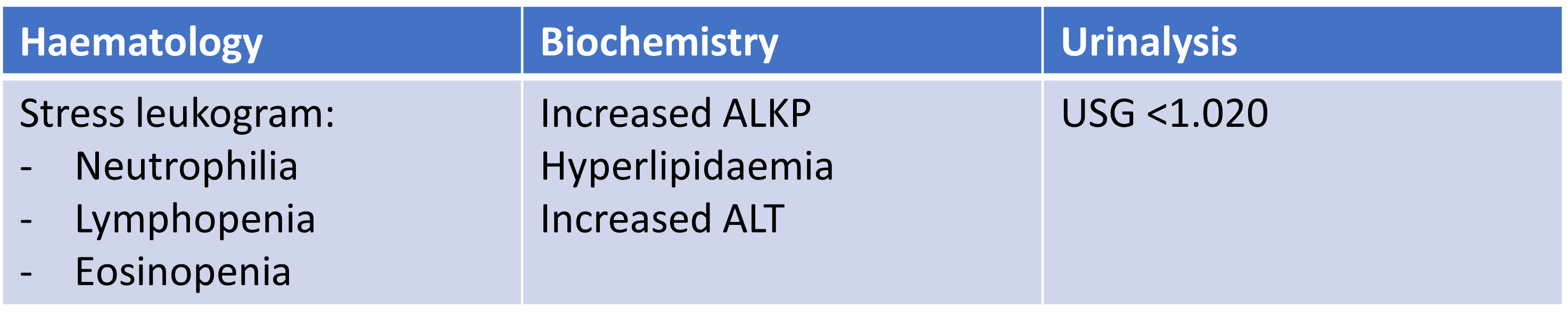

If signalment and clinical signs raise suspicion of Cushing’s syndrome, the next step is to undertake routine first-line investigations. The table below (adapted from Behrend et al, 2013) outlines the common abnormalities seen in after routine analysis of haematology, biochemistry and urine.

Not every dog with Cushing’s will show these clinical pathologies, but if we identify any, then that increases our suspicion.

With the history and initial work-up data, the question to ask for every case is: Is there enough evidence to test for Cushing’s?

addDiagnostic Testing

Once routine diagnostics have revealed non-specific indicators of Cushing's, the next step is to use specific diagnostic testing to confirm Cushing's syndrome.

Low Dose Dexamethasone Suppression Test (LDDST)

The 2012 ACVIM consensus statement (Behrend et al 2013) considers the LDDST to be the screening test of choice for Cushing’s disease, and it is the best test to use where your suspicion of Cushing’s is high.

This test may produce a false positive result, therefore you want to be sure that where a positive result is gained, it is due to true Cushing’s, rather than another nonadrenal illness. Where a negative result is gained, you can be very confident that the dog does not have Cushing’s.

ACTH Stimulation Test (ACTHST)

The ACTHST is unlikely to give a false positive result, but equally it can provide false negative values. Where a negative result is gained, further investigations may still be warranted as this test can miss truly Cushingoid dogs.

Alongside Vetoryl Dechra produce Cosacthen, the tetracosactide needed to perform the ACTHST.

addConfirming your suspicion

We want to be highly suspicious of Cushing’s before reaching for our endocrine test, meaning that the population of patients we are testing are likely to have the syndrome. Avoid “fishing” for Cushing’s in a patient unlikely to have it.

Which patients should I endocrine test?

Typical signalment

Consistent clinical signs

Consistent bloods and urinalysis

Which endocrine test should I use?

The low dose dexamethasone suppression test (LDDST) is the best test to use where your suspicion of Cushing’s is high. The 2012 ACVIM consensus statement (Behrend et al, 2013) considers the LDDST to be the screening test of choice for Cushing’s syndrome.

If a patient has a known concurrent disease, or Cushing’s is lower on the differentials list, the ACTH stimulation test (ACTHST) should be used.

Ask yourself, “If I perform an ACTHST in this patient and the result comes back negative, what is my next step?” If the answer is to go straight for the LDDST, your suspicion of Cushing’s is high, so why not choose the LDDST in the first place?